|

| |

| Girls Just Want to Go to School

| Cháu chỉ muốn được đi học

|

| By NICHOLAS D. KRISTOF Published: November 9, 2011 THU THUA, Vietnam | Nicholas D. Kristof 9/11/2011 Thời báo Niu-I-óc

|

|

| |

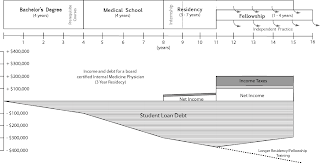

| Dao Ngoc Phung, center, is obsessed with education as a way for the family to get ahead. She devotes herself to overseeing the schoolwork by her younger brother, Tien, and sister, Huong.

| Đào Ngọc Phụng, đứng giữa, đinh ninh rằng học tập là một cách để cả gia đình để có thể tiến về phía trước. Cháu dành toàn tâm để trông coi việc học của em trai của mình, tên Tiến, và em gái, Hương.

|

| Sometimes you see your own country more sharply from a distance. That’s how I felt as I dropped in on a shack in this remote area of the Mekong Delta in Vietnam.

| Đôi khi bạn hiểu đất nước mình rõ hơn khi nhìn từ xa. Tôi chợt nghĩ như thế khi ghé thăm một căn chòi nhỏ ở miền đất hẻo lánh, vùng Châu thổ sông Cứu Long ở Việt Nam.

|

| The head of the impoverished household during the week is a malnourished 14-year-old girl, Dao Ngoc Phung. She’s tiny, standing just 4 feet 11 inches and weighing 97 pounds.

| Cô chủ gia đình nghèo khó này, Đào Ngọc Phụng là một bé gái mới 14 tuổi thiếu ăn suốt những ngày trong tuần. Cô bé người nhỏ xíu, cao chưa tới mét rưỡi và nặng chỉ 44 kg.

|

| Yet if Phung is achingly fragile, she’s also breathtakingly strong. You appreciate the challenges that America faces in global competitiveness when you learn that Phung is so obsessed with schoolwork that she sets her alarm for 3 a.m. each day.

| Tuy vậy, nếu như người Phụng mảnh mai đến đau lòng, thì cháu lại mạnh mẽ đến đáng phục. Bạn sẽ hiểu ra những thách thức mà nước Mỹ đang đối mặt về khả năng cạnh tranh toàn cầu khi bạn biết được rằng Phụng quyết tâm về việc học tập đến độ mỗi ngày cháu để đồng hồ báo thức để dậy lúc ba giờ sáng.

|

| She rises quietly so as not to wake her younger brother and sister, who both share her bed, and she then cooks rice for breakfast while reviewing her books.

| Cháu thường lặng lẽ thức dậy để khỏi làm em trai và em gái cùng ngủ chung giường phải thức giấc, rồi cháu vừa thổi cơm sáng vừa ôn bài.

|

| The children’s mother died of cancer a year ago, leaving the family with $1,500 in debts. Their father, a carpenter named Dao Van Hiep, loves his children and is desperate for them to get an education, but he has taken city jobs so that he can pay down the debt. Therefore, during the week, Phung is like a single mother who happens to be in the ninth grade.

| Mẹ cháu qua đời vì bệnh ung thư cách đây một năm, để lại cho gia đình món nợ khoảng 1.500 đô-la. Cha cháu, Đào Văn Hiệp, là thợ mộc, thương con và quyết tâm cho con đi học, nhưng ông phải lên thành phố làm nhiều công việc để có thể trả được nợ. Bởi vậy, suốt tuần, Phụng gánh trách nhiệm của một bà mẹ đơn thân dù chỉ mới học tới lớp chín.

|

| Phung wakes her brother and sister, and then after breakfast they all trundle off to school. For Phung, that means a 90-minute bicycle ride each way. She arrives at school 20 minutes early to be sure she’s not late.

| Phụng thức hai em dậy, ăn sáng xong thì cả ba chị em còng lưng đạp xe tới trường. Với Phụng, đó là một tiếng rưỡi đạp xe đến trường và một tiếng rưỡi đạp xe về nhà. Cháu thường xuyên tới trường trước 20 phút để chắc chắn khỏi bị trễ.

|

| After school, the three children go fishing to get something to eat for dinner. Phung reserves unpleasant chores, like cleaning the toilet, for herself, but she does not hesitate to discipline her younger brother, Tien, 9, or sister, Huong, 12. When Tien disobeyed her by hanging out with some bad boys, she thrashed him with a stick.

| Tan trường, ba chị em cùng đi bắt cá để kiếm cái ăn cho bữa tối. Phụng đảm đương những việc nặng nhọc trong nhà, như dọn rửa nhà vệ sinh, nhưng cháu cũng không do dự khi phải phạt em trai Tiến, 9 tuổi, và em gái Hương, 12 tuổi. Khi Tiến không nghe lời chị mà đi lêu lõng với mấy đứa bạn xấu, Phụng phạt roi em mình.

|

| Most of the time, though, she’s gentle, especially when Tien misses his mother. “I try to comfort him,” she says, “but then all three of us end up crying.”

| Tuy nhiên, thường thì cháu luôn dịu dàng, đặc biệt những lúc Tiến nhớ mẹ. “Con cố an ủi nó,” cháu kể, “nhưng rồi cả ba chị em ôm nhau khóc.” |

| Phung yearns to attend university and become an accountant. It’s an almost impossible dream for a village girl, but across East Asia the poor often compensate for lack of money with a dazzling work ethic and gritty faith that education can change destinies. The obsession with schooling is a legacy of Confucianism — a 2,500-year-old tradition of respect for teachers, scholarship and meritocratic exams. That’s one reason Confucian countries like China, South Korea and Vietnam are among the world’s star performers in the war on poverty.

| Phụng ao ước được đi học đại học và làm nhân viên kế toán. Đó là một giấc mơ gần như vô vọng đối với một cô gái nông thôn, nhưng ở các nước Đông Á, người nghèo thường bù đắp cho sựu túng thiếu của họ bằng sự siêng năng làm việc đến mức đáng kinh ngạc và với lòng tin bền bỉ rằng học vấn có thể làm số phận họ đổi thay. Sự say mê học hành đến mức ám ảnh là một di sản của Khổng giáo – một truyền thống tôn sư trọng đạo đã có 2.500 năm nay, đề cao việc học và thi cử để chọn tài năng. Đó là lời giải thích tại sao những nước Khổng giáo như Trung Quốc, Hàn Quốc và Việt Nam đều đạt thành tích hàng đầu thế giới trong cuộc chiến chống nghèo đói.

|

| Phung pleads with her father to pay for extra tutoring in math and English. He explains softly that the cost — $40 a year — is unaffordable.

| Phụng xin cha cho tiền học thêm toán và tiếng Anh. Song cha cháu nhẹ nhàng giải thích rằng tiền học – khoảng 40 đô mỗi năm – là quá đắt nên không thể cho cháu học.

|

| (For anyone who wants to help Phung, an aid group called Room to Read has set up a fund to help her and girls like her; details are on my blog, nytimes.com/ontheground, or on Facebook.com/Kristof.) | (Với những ai muốn giúp đỡ Phụng, đã có một quỹ hỗ trợ tên là Room to Read được lập ra để giúp cháu và những cháu gái khác có hoàn cảnh tương tự; xin xem chi tiết trên blog của tôi, nytimes.com/ontheground, hoặc trên Facebook.com/Kristof.)

|

| I wish we Americans could absorb a dollop of Phung’s reverence for education. The United States, once the world leader in high school and college attendance, has lagged in both since the 1970s. Of 27 countries in the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development for which we have data, the United States now ranks 23rd in high school graduation rates.

| Tôi ước rằng người Mỹ chúng ta có thể tiếp thu phần nào ý thức tôn trọng học vấn của cháu Phụng. Hoa kỳ, vốn là nước dẫn đầu thế giới về tỉ lệ học sinh học trung học và đại học, nhưng đã tụt hậu về cả hai mặt này kể từ những năm 1970. Trong 27 nước thuộc Tổ chức Hợp tác và Phát triển Kinh tế (OECD) mà chúng ta hiện có số liệu, thì Hoa Kỳ đang xếp thứ 23 về tỉ lệ tốt nghiệp trung học.

|

| Granted, Asian schools don’t nurture creativity, and Vietnamese girls are sometimes treated as second-class citizens who must drop out of school to help at home. But education is generally a top priority in East Asia, for everyone from presidents to peasants.

| Cho dù trường học ở Châu Á không nuôi dưỡng sáng tạo, và các cháu gái Việt Nam đôi lúc bị coi như công dân hạng hai, phải bỏ học để đỡ đần gia đình, nhưng giáo dục vốn là ưu tiên hàng đầu ở Đông Á, đối với tất cả mọi người từ các vị chủ tịch cho tới nông dân.

|

| Teachers in America’s troubled schools complain to me that parents rarely show up for meetings. In contrast, Phung’s father takes a day off work and spends a day’s wages for transportation to attend parent-teacher conferences.

| Ở Mỹ giáo viên dạy các trường có vấn đề thường than phiền với tôi rằng phụ huynh học sinh ít khi đi họp. Ngược lại, cha Phụng đã nghỉ một ngày làm, và dành một ngày lương mua vé xe để đi họp phụ huynh cho con.

|

| “If I don’t work, I lose a little bit of money,” he said. “But if my kids miss out on school, they lose their life hopes. I want to know how they’re doing in school.”

| “Nếu tôi nghỉ làm, tôi có mất chút tiền,” ông nói. “Nhưng nếu con tôi lơi là học tập, thì sẽ đánh mất hy vọng của cả đời chúng. Tôi muốn biết con mình học hành thế nào ở trường.”

|

| “I tell my children that we don’t own land that I can leave them when they grow up,” he added. “So the only thing I can give them is an education.”

| “Tôi bảo các con rằng nhà mình không có đất đai để lại cho con cái khi lớn lên,” ông nói tiếp. “Cho nên, cái duy nhất mà tôi có thể cho chúng là học vấn.” |

| For all the differences between Vietnam and America, here’s a common truth: The best way to sustain a nation’s competitiveness is to build human capital. I wish we Americans, especially our politicians, could learn from Phung that our long-term strength will depend less on our aircraft carriers than on the robustness of our kindergartens, less on financing spy satellites than on financing Pell grants.

| Cho dù giữa Việt Nam và Mỹ có biết bao khác biệt, những vẫn có một chân lý chung này: Cách tốt nhất để duy trì sức cạnh tranh của một quốc gia là xây dựng nguồn vốn con người. Tôi ước gì người Mỹ chúng ta, đặc biệt là các chính khách, có thể học được từ cháu Phụng rằng sức mạnh lâu dài của chúng ta sẽ phụ thuộc ít hơn vào các tàu sân bay, và phụ thuộc nhiều hơn vào sự vững mạnh của hệ thống nhà trẻ, phụ thuộc ít hơn vào việc chi tiêu cho các vệ tinh do thám, và phụ thuộc hơn vào việc tài trợ cho các học bổng Pell*.

|

| The Federal Pell Grant Program provides need-based grants to low-income undergraduate and certain postbaccalaureate students. | *Chương trình học bổng Liên bang dành cho các sinh viên đại học và một số học sinh tốt nghiệp trung học thuộc gia đình có thu nhập thấp

|

| Phung gets this better than our Congress. Every day, she helps her little brother and sister with their homework first and then completes her own. Sometimes she doesn’t collapse into bed until 11 p.m., only to rouse herself four hours later.

On Sundays, Phung sleeps in. As she explained: “I don’t get up till 5.” | Phụng hiểu điều này rõ hơn Quốc hội chúng ta. Ngày ngày, cháu giúp hai em làm học bài trước, rồi làm bài của mình sau. Có khi mãi tới 11 giờ đêm cháu mới đi ngủ, để rồi bốn tiếng sau lại thức dậy học.

Ngày chủ nhật, Phụng thường ngủ ráng. Cháu giải thích: “5 giờ con mới dậy lận.”

|

|

| Chuyển ngữ: Nguyễn Quang

|

| http://www.nytimes.com/2011/11/10/opinion/kristof-girls-just-want-to-go-to-school.html?_r=4&emc=tnt&tntemail0=y | |

Dưới đây là một bản dịch khác của le-na, với giọng văn rất truyền cảm

| Girls Just Want to Go to School - Con chỉ muốn đi học Dao Ngoc Phung, center, is obsessed with education as a way for the family to get ahead. She devotes herself to overseeing the schoolwork by her younger brother, Tien, and sister, Huong. Sometimes you see your own country more sharply from a distance. That’s how I felt as I dropped in on a shack in this remote area of the Mekong Delta in Vietnam. The head of the impoverished household during the week is a malnourished 14-year-old girl, Dao Ngoc Phung. She’s tiny, standing just 4 feet 11 inches and weighing 97 pounds. Yet if Phung is achingly fragile, she’s also breathtakingly strong. You appreciate the challenges that America faces in global competitiveness when you learn that Phung is so obsessed with schoolwork that she sets her alarm for 3 a.m. each day. She rises quietly so as not to wake her younger brother and sister, who both share her bed, and she then cooks rice for breakfast while reviewing her books. The children’s mother died of cancer a year ago, leaving the family with $1,500 in debts. Their father, a carpenter named Dao Van Hiep, loves his children and is desperate for them to get an education, but he has taken city jobs so that he can pay down the debt. Therefore, during the week, Phung is like a single mother who happens to be in the ninth grade. Phung wakes her brother and sister, and then after breakfast they all trundle off to school. For Phung, that means a 90-minute bicycle ride each way. She arrives at school 20 minutes early to be sure she’s not late. After school, the three children go fishing to get something to eat for dinner. Phung reserves unpleasant chores, like cleaning the toilet, for herself, but she does not hesitate to discipline her younger brother, Tien, 9, or sister, Huong, 12. When Tien disobeyed her by hanging out with some bad boys, she thrashed him with a stick. Most of the time, though, she’s gentle, especially when Tien misses his mother. “I try to comfort him,” she says, “but then all three of us end up crying.” Phung yearns to attend university and become an accountant. It’s an almost impossible dream for a village girl, but across East Asia the poor often compensate for lack of money with a dazzling work ethic and gritty faith that education can change destinies. The obsession with schooling is a legacy of Confucianism — a 2,500-year-old tradition of respect for teachers, scholarship and meritocratic exams. That’s one reason Confucian countries like China, South Korea and Vietnam are among the world’s star performers in the war on poverty. Phung pleads with her father to pay for extra tutoring in math and English. He explains softly that the cost — $40 a year — is unaffordable. (For anyone who wants to help Phung, an aid group called Room to Read has set up a fund to help her and girls like her; details are on my blog, nytimes.com/ontheground, or onFacebook.com/Kristof.) I wish we Americans could absorb a dollop of Phung’s reverence for education. The United States, once the world leader in high school and college attendance, has lagged in both since the 1970s. Of 27 countries in the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development for which we have data, the United States now ranks 23rd in high school graduation rates. Granted, Asian schools don’t nurture creativity, and Vietnamese girls are sometimes treated as second-class citizens who must drop out of school to help at home. But education is generally a top priority in East Asia, for everyone from presidents to peasants. Teachers in America’s troubled schools complain to me that parents rarely show up for meetings. In contrast, Phung’s father takes a day off work and spends a day’s wages for transportation to attend parent-teacher conferences. “If I don’t work, I lose a little bit of money,” he said. “But if my kids miss out on school, they lose their life hopes. I want to know how they’re doing in school.” “I tell my children that we don’t own land that I can leave them when they grow up,” he added. “So the only thing I can give them is an education.” For all the differences between Vietnam and America, here’s a common truth: The best way to sustain a nation’s competitiveness is to build human capital. I wish we Americans, especially our politicians, could learn from Phung that our long-term strength will depend less on our aircraft carriers than on the robustness of our kindergartens, less on financing spy satellites than on financing Pell grants. Phung gets this better than our Congress. Every day, she helps her little brother and sister with their homework first and then completes her own. Sometimes she doesn’t collapse into bed until 11 p.m., only to rouse herself four hours later. On Sundays, Phung sleeps in. As she explained: “I don’t get up till 5.”

| Girls Just Want to Go to School - Con chỉ muốn đi học Cô bé Đào Ngọc Phụng, đứng giữa, luôn hằng mong được theo đuổi con đường học vấn để giúp gia đình thoát khỏi cảnh khốn khó. Cô bé đảm trách luôn việc trông nom em trai, Tiến và em gái, Hương trong việc học hành. Đôi khi, bạn sẽ nhìn nhận về tổ quốc mình sâu sắc hơn khi quan sát nó từ một nơi xa. Đó là điều mà tôi cảm nhận được khi ghé vào túp lều xiêu vẹo trong khu vực hẻo lánh của Đồng bằng sông Cửu Long, Việt Nam. Trong suốt tuần lễ tôi có mặt ở đây, chủ của gia đình nghèo khó này là Đào Ngọc Phụng, một cô bé 14 tuổi gầy nhom. Cô gái bé nhỏ, chỉ cao chừng mét rưỡi (4 feet 11 inches = 1,4986 m) và nặng 44kg (97 pounds = 43,99 kg) Tuy Phụng gầy gò ốm yếu là vậy, nghị lực của cô bé quả là phi thường. Bạn sẽ đánh giá được những thách thức mà nước Mỹ gặp phải trong quá trình cạnh tranh toàn cầu khi bạn chứng kiến cô bé Phùng ham học hàng ngày thức dậy học bài từ lúc 3h sáng. Cô bé rón rén thức dậy vì sợ làm em trai và em gái ngủ chung giường thức giấc. Sau đó cô bé vừa nấu cơm sáng vừa tranh thủ học bài. Mẹ các em mất năm ngoái do căn bệnh ung thư, để lại khoản nợ cho gia đình lên tới hơn 30 triệu ($1,500). Bố các em, anh Đào Văn Hiệp, làm nghề thợ mộc, vốn rất yêu các con và nỗ lực hết sức để con mình được đến trường. Tuy nhiên, ông phải lên thành phố kiếm tiền trả nợ. Vậy nên, suốt cả tuần, Phụng là “bà mẹ đơn thân” mới học lớp 9. Phùng đánh thức các em, và sau khi ăn sáng, mấy chị em hối hả đi học. Với Phụng, quãng đường đi học mất tới 90 phút đạp xe. Cô bé tới trường sớm 20 phút để không muộn học. Tan học, 3 chị em đi câu cá để có thức ăn cho bữa tối. Phụng đảm đương mọi công việc cực nhọc trong nhà, như là lau chùi hố xí, nhưng cô bé luôn giữ kĩ luật với cậu em trai tên Tiến, 9 tuổi, và em gái, Hương, 12 tuổi. Khi Tiến không vâng lời, bỏ đi chơi với bọn con trai lêu lổng ngoài đường, bà chị lấy gậy vụt cho cậu em một trận. Song đó chỉ là đôi khi, bình thường bà chị rất dịu dàng với cậu em, nhất là khi Tiến nhớ mẹ. Cô bé kể: “Cháu tìm cách an ủi nó”, “Cơ mà cuối cùng thì 3 chị em òa khóc luôn” Phụng khao khát được đi học đại học và trở thành kế toán. Đây là giấc mơ khó lòng thành hiện thực đối với một cô bé vùng quê nghèo khó. Nhưng khắp khu vực Đông Á, người nghèo thường bù đắp khoảng trống thiếu thốn về vật chất bằng đức tin kiên định trong tâm khảm rằng vốn học thức có thể giúp người ta thay đổi vận mệnh. Khao khát được học hành là di sản của Nho giáo - với truyền thống 2500 năm tôn sư trọng đạo, mến mộ học thức và các kì thì tìm kiếm nhân tài. Đó là một lý do giả thích vì sai những đất nước chịu ảnh hưởng của Nho giáo như Trung Quốc, Hàn Quốc và Việt Nam là những ngôi sao sáng trong cuộc chiến chống đói nghèo. Phụng xin bố tiền đi học thêm toán và tiếng Anh. Bố em nhẹ nhàng bảo em rằng tiền học – 800 ngàn đồng ($ 40) một năm- là lớn quá, nhà mình không kham nổi. (Bạn đọc có lòng hảo tâm muốn giúp đỡ Phụng thì xin vui lòng liên hệ với nhóm “Room to Read”, nhóm vừa lập quỹ để giúp đỡ Phụng và những cô bé có hoàn cảnh như em; mọi chi tiết có trên blog của tôi nytimes.com/ontheground, hay địa chỉ facebook Facebook.com/Kristof ) Tôi ước gì người Mỹ cũng có được lòng hiếu học như Phụng. Nước Mỹ, quốc gia từng dẫn đầu thế giới về tỷ lệ học sinh theo học phổ thông trung học và đại học, đã tụt lại phía sau từ thập niên 70. Theo số liệu mà chúng tôi hiện có, nước Mỹ nay chỉ đứng thứ 23 trong số 27 nước thuộc Tổ chức hợp tác và phát triển kinh tế (OECD) về tỉ lệ học sinh tốt nghiệp phổ thông trung học. Mặc dù vậy, các trường học ở châu Á không ươm mầm sự sáng tạo, và nữ sinh Việt đôi khi bị đối xử như là công dân hạng hai, các em phải bỏ học để giúp đỡ gia đình. Song, nhìn chung, giáo dục vẫn được coi là ưu tiên hàng đầu ở Đông Á, từ lãnh đạo cho tới dân thường. Các giáo viên ở các trường giáo dục đặc biệt (troubled schools: trường học cho các trẻ em gặp vấn đề trong tâm lý hoặc khả năng nhận biệt) phàn nàn với tôi rằng các bậc cha mẹ ở đây hiếm khi đi họp phụ huynh. Ngược lại, bố Phụng đã nghỉ một ngày công và dành hẳn một ngày lương để bắt xe về họp phụ huynh. Ông tâm sự: “Nếu không đi làm một ngày, tôi mất một khoản tiền lương nhỏ. Nhưng mà nếu các con tôi không được đi học, chúng sẽ không còn cơ hội nào vươn lên trong cuộc sống. Tôi muốn biết được việc học tập ở trường của các con ra sao.” Ông nói thêm “Tôi bảo chúng rằng nhà mình không có đất đai để bố có thể cho các con khi trưởng thành. Nên bố chỉ có thể cho các con cơ hôi học hành mà thôi.” Bỏ qua tất cả điểm khác biệt giữa Việt Nam và Mỹ, có một sự thật chung cho cả hai nước là: Cách tốt nhất để duy trì năng lực cạnh tranh của quốc gia là xây dựng nguồn lực con người. Tôi ước mong sao người Mỹ, đặc biệt là các chính trị gia, có thể học hỏi từ Phụng một điều rằng sức mạnh bền bỉ của chũng ta không phụ thuộc nhiều vào các tàu sân bay mà phụ thuộc vào sự mạnh mẽ của các nhà trẻ, mẫu giáo, ít phụ thuộc vào các vệ tinh gián điệp mà trông chờ vào việc cung cấp tài chính cho các chương trình Pell grants (chương trình trợ cấp của chính phủ dành cho sinh viên có hoàn cảnh khó khăn). Phụng hiểu điều này tốt hơn Quốc hội Mỹ. Hàng ngày, cô bé hướng dẫn các em làm bài tập trước rồi mới đến lượt mình. Thỉnh thoảng, cô bé thức mãi cho tới 11h đêm mới ngãmình xuống giường và 4 tiếng sau lại thức dậy rồi. Vào chủ nhật, Phụng cho phép mình ngủ nướng thêm tí. “Cháu ngủ cho tới 5h mới dậy”, cô bé kể.

|